How to Depict Multi-generational Family Tree With Multiple Stepfamilies

Today, more than than four-in-ten American adults have at least one pace relative in their family – either a stepparent, a step or half sibling or a stepchild, according to a nationwide Pew Research Center survey. People with step relatives are merely equally likely as others to say that family is the near important chemical element of their life. Yet, they typically feel a stronger sense of obligation to their biological family members (be it a parent, a kid or a sibling) than to their footstep relatives, the survey finds.

Several sweeping changes in the demography of American family life in the past half century – including increases in divorce and in the share of babies born out of wedlock – accept contributed to the prevalence of step relatives.

Several sweeping changes in the demography of American family life in the past half century – including increases in divorce and in the share of babies born out of wedlock – accept contributed to the prevalence of step relatives.

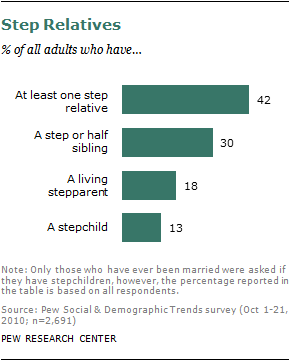

Among the 2,691 adults surveyed by the Pew Research Middle from October 1-21, 2010, 42% say they have at to the lowest degree one step relative. 3-in-ten have a pace or half sibling, 18% have a living stepparent, and 13% have at to the lowest degree one stepchild.1

Having a stepfamily is not something most people anticipate or plan for, and that is reflected in the survey findings. When asked whether their family life has turned out about as they expected or if information technology is different than they expected, a 54% majority of those who have at least one pace relative say things have turned out differently than they expected. This compares with only 41% of those who have no pace relatives.

Still, dissimilar doesn't necessarily mean worse. Seven-in-10 adults who have at least one stride relative say they are very satisfied with their family unit life. Those who don't have any pace relatives register slightly higher levels of family satisfaction (78% very satisfied).

Still, dissimilar doesn't necessarily mean worse. Seven-in-10 adults who have at least one stride relative say they are very satisfied with their family unit life. Those who don't have any pace relatives register slightly higher levels of family satisfaction (78% very satisfied).

In the Pew Research survey, all married adults were asked to compare the closeness of their own marriage with that of their parents' marriage when they were growing upward. Among married adults with no step relatives, 45% say their marriage is closer than their parents' wedlock was, while 50% say their wedlock is about the same as their parents'. By dissimilarity, amid married adults who take step siblings or stepparents – many of whom presumably had divorced parents –more than half dozen-in-ten say their marriage is closer than their parents' marriage was, while roughly 30% say it'south about the same.

Demographic Patterns

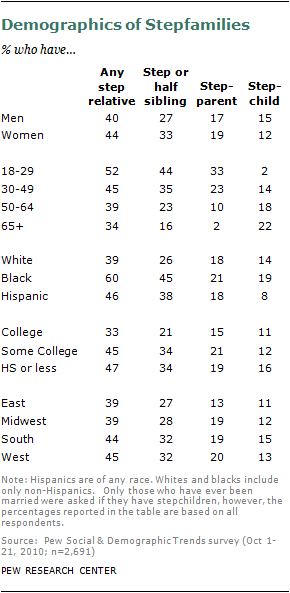

Stepfamilies tin be found among young and onetime, black and white, and rich and poor. However, in that location is a singled-out demographic pattern in the incidence of stepfamilies among American adults. Young people, blacks, and those without a college degree are significantly more likely to have step relatives. Among those under historic period 30, more than half (52%) report that they have at to the lowest degree 1 footstep relative. This compares with 40% of those ages 30 and older (including but 34% of those ages 65 and older).

This is not surprising given that young adults are much more probable than their older counterparts to have grown upward with parents who were not married. In the Pew Inquiry survey, 36% of those nether age thirty said during the fourth dimension they were growing up their parents were either divorced, separated or were never married. This compares with 21% of those ages 30-49 and only 10% of those ages l and older.

A higher share of blacks than whites or Hispanics have step family unit members. Among black adults interviewed in the Pew Research survey, sixty% take at least one pace relative. This compares with 46% of Hispanics and 39% of whites. The biggest gap between blacks and whites is in the proportion of each that has step or half siblings. Some 45% of black adults report having at least i step or half sibling, compared with 26% of whites. Roughly the same proportion of blacks and whites have a living stepparent. And blacks are somewhat more likely than whites to take stepchild.

Among blacks, at that place is a big gap in the percent of men and women who report that they have stepchildren. One-in-four black men (24%) say they have a stride kid, compared with xiv% of black women. Black men are likewise much more likely than white (xv%) or Hispanic men (seven%) to say they have stepchildren.

In addition to age and race, socioeconomic status is linked to the prevalence of stepfamilies. Simply a third of higher graduates say they have at least 1 stride relative. Past dissimilarity, 46% of those without a higher caste have a step relative. Similarly, stepfamilies are less common amongst those with higher household incomes. While 36% of those with almanac incomes of $75,000 or college say they have at least one step relative, 43% of those making between $30,000-$74,999, and fully half of those with almanac incomes of less than $xxx,000 say they have step family members.

Previous Pew Research Heart analysis revealed a steady decline over the past 50 years in the share of American adults who are married.ii Co-ordinate to that assay, the falloff in marriage rates has been more dramatic among certain demographic groups – and those are the same groups that are more probable to be living in stepfamilies today.

For example, blacks are much less likely to be married today than they were 50 years ago. In 1960, 61% of blacks ages xviii and older were married; by 2008 only 32% were married. Union rates have besides declined amongst whites and Hispanics over the same time period though not as sharply. In improver, a large marriage gap has emerged betwixt college graduates and those without a college degree. Today, marriage remains the norm for higher graduates, while fewer than half of those who did not graduate from college are currently married.

Step Relatives and Family unit Obligation

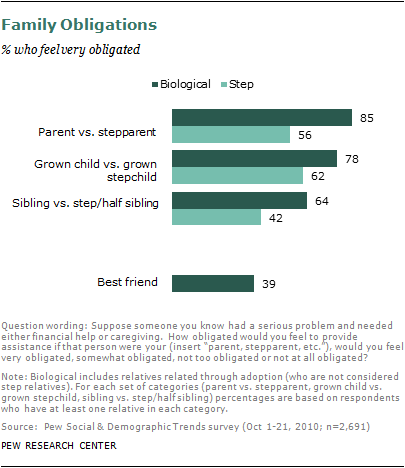

Virtually adults who have stride relatives feel a stronger sense of obligation to their biological family members than they do to their step kin.3 The Pew Research survey asked respondents how obligated they would feel to provide assistance to family members who were dealing with a serious problem and needed either financial help or caregiving. Survey respondents were asked near a list of family unit members including parents, siblings, children, stepparents, pace or half siblings and stepchildren. They were also asked how obligated they would feel to help out their best friend.

Overall, parents rank the highest in the hierarchy of family obligations – 83% of those with a living parent say they would feel very obligated to provide help to their parent if he or she was faced with a serious trouble. Amongst adults who have both a living parent and a living stepparent, 85% say they would feel very obligated to help out their parent, while 56% say they would feel a similar sense of obligation toward their stepparent.

Overall, parents rank the highest in the hierarchy of family obligations – 83% of those with a living parent say they would feel very obligated to provide help to their parent if he or she was faced with a serious trouble. Amongst adults who have both a living parent and a living stepparent, 85% say they would feel very obligated to help out their parent, while 56% say they would feel a similar sense of obligation toward their stepparent.

Parents feel near as obligated to their grown children every bit adult children feel to their aging parents. Overall, 77% of parents with at least 1 grown child say they would feel very obligated to aid that child if need be.

Among adults who take both a grown biological kid and a grown stepchild, the biological child exerts a stronger pull. About eight-in-x (78%) of these parents say they would feel very obligated to provide assistance to a grown child. Closer to six-in-ten (62%) say they would feel equally obligated to their grown stepchild.

Similarly, adults are more inclined to come to the aid of their biological siblings than they are to assist their pace or half siblings. Among those who have both biological siblings and step or half siblings, 64% say they would feel very obligated to a sibling who was in serious trouble. Only 42% say they would feel very obligated to provide help to a step or one-half sibling.

Yet, even though step relatives trail biological relatives in each of these measures, they do slightly ameliorate overall than "best friend." No thing what their family constellation, all survey respondents were asked how obligated they would feel to assist their all-time friend if he or she was faced with a serious problem. Just 39% of adults say they would feel very obligated.

Nearly the Data

Results for this survey are based on telephone interviews conducted with a nationally representative sample of two,691 people ages 18 and older living in the continental United States. A combination of landline and cellular random digit dial (RDD) samples was used to stand for all adults in the continental United States who have access to either a landline or cellular telephone. A total of 1,520 interviews were completed with respondents contacted past landline telephone and 1,171 with those contacted on their cellular phone. The data are weighted to produce a final sample that is representative of the full general population of adults in the continental The states.

- Interviews were conducted Oct 1-21, 2010.

- Margin of sampling error is plus or minus two.6 percentage point for results based on the total sample at the 95% confidence level.

- Survey interviews were conducted in English language and Spanish under the direction of Princeton Survey Enquiry Associates International.

gutierrezpokenderyind.blogspot.com

Source: https://www.pewresearch.org/social-trends/2011/01/13/a-portrait-of-stepfamilies/

0 Response to "How to Depict Multi-generational Family Tree With Multiple Stepfamilies"

Post a Comment